Audiences have been long deprived of narrative diversity in mainstream cinema. And, during the last decade, it’s been evident that LGBTQ directors and Black filmmakers are over it too.

But, no longer sequestered to their distinct corners of “queer movies” or “Black TV shows,” Black directors have carved out an authentic space for themselves and their queer characters, center stage.

Dee Rees

She is a modern-day phenomenon. Dee Ree’s first feature film, “Pariah,” garnered critical acclaim and adoration from audiences that have stayed with her.

The movie follows Alike, a Black girl navigating her sexuality in a household not interested in who she really is. Still, never wavers on the assuredness of her own identity. And becomes a beacon of bravery and pride in an oppressive world where the genre is often fraught with doubt.

Rare and beautiful, Pariah draws inspiration from Rees’ own experiences coming into a queer identity to her family. Shortly after finishing NYU’s film program, she came out as a lesbian to her parents. And, in the decade that followed, neither parent spoke to her.

Meanwhile, she hustles to make a name for herself in the industry until they saw “Pariah” for the first time.

“Pariah,” won over a dozen awards. And Rees has been sprinting towards the next masterpiece ever since. Her biopic Bessie scored her an Emmy nomination. Likewise, “Mudbound,” her second feature and an Oscar nominee.

Still, her success hasn’t slowed the director down at all. Anything could be next for Rees.

Justin Simien

Dear White People made waves on Netflix during the pandemic. Perhaps that is because the show picked up the right creator and director, Justin Simien.

Coming from Houston, Texas, Simien grew up in a diverse, bustling city. He cites his subsequent move to Chapman University as the culture shock that inspired Dear White People.

However, finding himself in a majority white environment did not end there. He likens times to what it’s like to work in Hollywood today, where he still frequently finds himself the only queer Black voice in the room.

We’ve been kind of screaming at a wall and hearing all sorts of commentary… ‘Are we past all of this? Why are you making this about race?’ All of the sort of typical racial gaslighting that a Black person experiences in their life, this show has experienced.

Justin Simien for Deadline, 2020

And, perhaps Dear White People reflects Simiens attitude the best. The show is about a group of students of color at Winchester University. Together, the navigatage the serious stakes of injustice, politics, and activism, but it’s funny.

The show, like Simiens, doesn’t let racism and naivety exhaust the group’s energy (though they’d have every right). Instead, the show is a celebration of passion and camaraderie from which the audience can draw strength.

Still, Simiens recalls that before the Black Lives Matter movement, the show experienced all sorts of criticism. In fact, a few months prior he was told that networks didn’t need another show like his right now. The movement spiked the show’s viewership, still its success this past summer is complex.

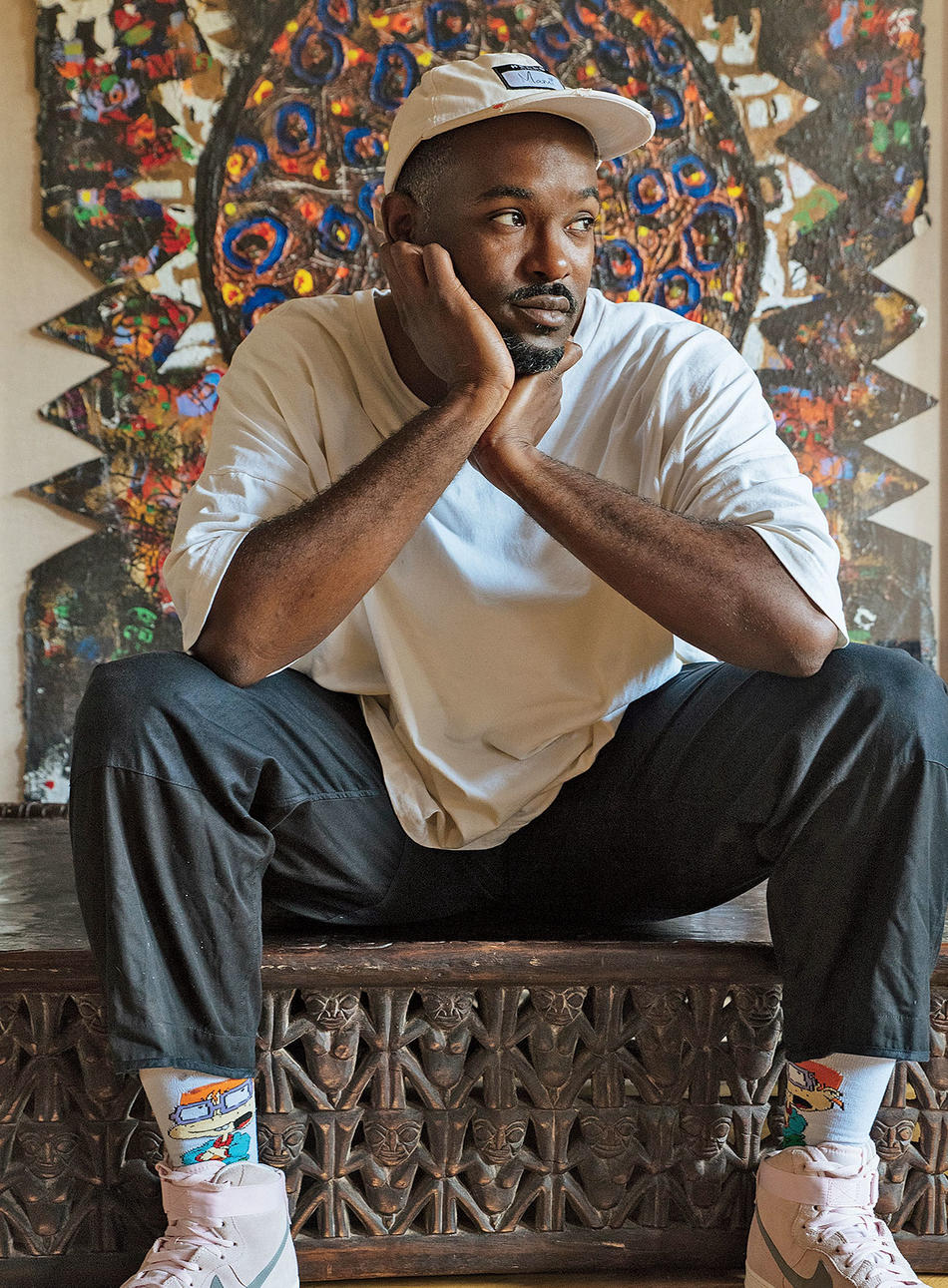

Elegance Bratton

As his name might suggest, Elegance Bratton, imbues his work with the utmost grace.

And, although Bratton has made himself comfortable in the success of his award-winning short films, and feature-length PIER KID, he experienced no such affirmation growing up.

PIER KIDS is inspired by Bratton’s own experiences growing up homeless after thrown out of his mother’s house in New Jersey for being gay.

The movie depicts three homeless queer characters who live through trials of prostitution, welfare, and familial ties. Similar to Bratton’s own experience for 10 years before he joined the Marines.

This to me is the spirit of Black gay life. Knock me down? Sure, I’ll play dead, but when I get back up, game’s over.

Elegance Bratton for the New York Times, 2018

During his time in the Marine Corps, Bratton learned to handle a camera by shooting weapon demonstration videos and photographing the troops. Later, he attended Columbia University double majoring in African American Studies and Anthropology.

This time deeply affected Bratton’s creative work. Thus, he took it upon himself to bring a sense of Black, queer community to the screen as an LGBTQ director.

And, set out on a mission to reframe the narrative that Black queer people. Shifting the narrative away from victims of systematic oppression, to resilience heroes.

Since his graduation, he has published photography books and shot short films. But, he is mostly known for the documentary series about house ballroom culture in New York a la Paris is Burning.

Just as in PIER KIDS, Elegance Bratton’s work is undeniably saturated with awareness and sensitivity.

Wanuri Kahiu

The first Kenyan film to screen at Cannes Film Festival, Rafiki is a film of innocent love directed by Wanuri Kahiu.

Kahiu, who is Kenyan herself, describes the film as a work of “Afrobubblegum,” which aims to depoliticize Black joy.

But outside of the dreamlike teenage love story of Rafiki, politics run rampant about Kahiu. The film was banned from Kenya on the grounds of its “homosexual theme and clear intent to promote lesbianism.”

The film is a love story, the filmmaker’s effort to remove the narrative of war and poverty from which Africa is normally depicted. Thus, fighting for her own rights and that of her peers, Kahiu sued her home country.

I was exploring the idea of the choices you have to make if you are in a same-sex relationship between love and courage — between love and safety. If you choose one, you’re definitely not choosing the other.

Wanuri Kahiu for CNN, 2019

Kahiu has said that it was simply the most beautiful, tender story she had ever heard. And, the fact that it occurred between two teenage girls was secondary.

Though she never intended to make it as a political statement, the movie’s commentary highlighted Africa’s politics more than any other. Kahiu is taking it all in.

“I feel like I’m just getting started,” she says. Without completely being able to identify how Kahiu identifies, we wanted to still highlight the director’s amazing work with representation of the LGBTQ community.

Why we need more LGBTQ directors:

As our culture continues to move towards a more equitable future across identities, elevating the voices of LGBTQ directors and the creative community is an integral part of the process.

Not only has systemic injustice prevented Black filmmakers and LGBTQ directors from making works that honestly reflect and speak to the experiences of Black people in America, but queerness as part of the narrative has also remained entirely out of the question.

Black queer filmmakers have worked tirelessly on our behalf, not only recognizing those who often feel they aren’t allowed community, but opening up the potential for unique experiences to inform the ever-diversifying archive of creative work.

:format(jpeg)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/55911339/1_FwTuHB8RxApe1h_IlylQdQ.0.jpeg)