Mexican cartels and the violence that consumes them have long overshadowed the vibrancy of regions like Tijuana and Michoacán. The Cartel Project, a global network of journalists covering Mexican drug cartels and their political connections, is dedicated to ensuring the safety of journalists and their stories.

Organized crime undermines political infrastructure, and economic instability is at an all-time high. Thus, Mexico has earned the grim title of being the most dangerous country in the world for journalists.

In fact, since 2000, 119 journalists have been killed in Mexico alone. Yet, these media heroes have persevered despite the lack of hostility of the environments they work in.

After years of being exposed to crime and violence, these are their stories.

What are “fixers?”

Because of the risk journalists run, while accounting for projects on cartels, they’ve developed a few strategies to ensure that they and the story can get out safely.

For example, journalists looking to report on stories unfolding in Mexico go through a “fixer.”

A fixer is a journalist from the local area being reported that helps the foreign journalist with the whereabouts of the place. They are the most effective way for a foreign journalist to get local news without causing too much attention.

Basically, they are looking for someone with good contacts who understands the unwritten rules of the city — like which neighborhoods are safe to go to, how to speak with drug dealers or human smugglers, those types of things.

Jorge Nieto, a Tijuana-based independent journalist who also works as a fixer. San Diego Union Tribune, 2019

These “fixers” can be from anywhere and make between $300 to $450 a day (more than local journalists in Mexico make in a week).

However, this is not risk-diminishing but, instead, risk-shifting. Fixers often receive the brunt of journalist’s most naive power plays.

A study conducted by Harvard on the relationship between journalists and fixers revealed that more than 70 percent of journalists say they never placed a fixer in immediate danger, while 56 percent of fixers stated that they were always or often in danger.

Yet, more often than not, these media heroes rarely receive the light or the credit that they deserve.

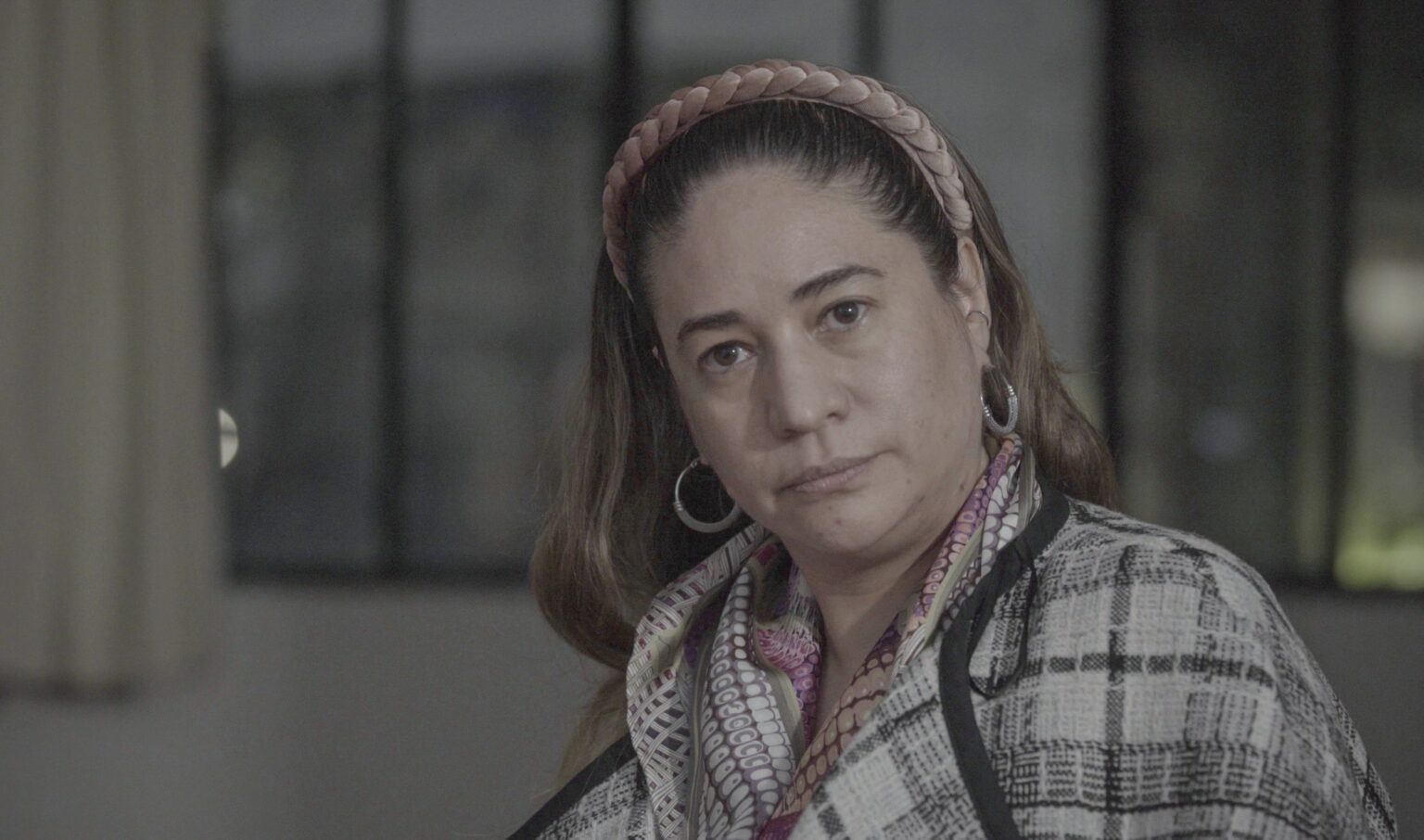

Deborah Bonello

Deborah Bonello is one of the figures helping to shed light on the drug and sex trafficking crimes unfolding across Latin America.

Currently the senior editor for Latin America at VICE world news, she boasts an expansive background working for the LA Times, the Financial Times, and also InSight Crime.

Their requests are like a wish list to Santa Claus.

Gaby Martinez, Tijuana-based fixer and journalist, speaking of publications reaching out to her as a fixer. San Diego Union Tribune 2019

An award-winning producer and videographer, Bonello continues to do the important work of bringing attention to crime in Latin America. She recently founded the Mexican Reporter, where she archives her work on the matter.

Her most recent work investigates the context for a video in which gang members can be seen parading weapons. Bonello illuminates how this visual display of weaponry is likely directed towards local authorities just to make them feel vulnerable.

Moreover, another one of her works investigates cartel shootings of drug rehabilitation centers. Martinez connected the dots and revealed local cartel chapters warring over the monopoly of the region’s drug market. These chapters had been inflicting violence to ensure consumer’s loyalty.

Undeniably, Bonello is doing the heavy lifting job concerning the international stage for cartel projects. Not to mention, she is also a heroic fixer, helping other journalists report on Mexico’s criminal activity as well.

And, while local journalists hold it down on the front lines of violence, the international press community has banded together in order to protect their contributors.

The Cartel Project

The Cartel Project is a global network of journalists covering Mexican drug cartels and their political connections.

Members of The Cartel Project are attempting to deter hostility towards journalists by coordinating a publication of investigations on the cartel across 25 different major media outlets.

Therefore, even if a single journalist is targeted, they will be backed by 25 institutions that are set to release their story at the same time. It all leads to an essential truth.

Killing the journalist won’t kill the story.

The Cartel Project mission statement

The project is coordinated by Forbidden Stories. And, it comes after the death of journalist Regina Martinez, who was murdered in her own home.

Regina Martinez

Regina Martinez was a trailblazing journalist during the ’90s. She embarked on dangerous missions to reveal corruption and violence in Veracruz, Mexico.

Martinez was also a journalist known for working around the clock to investigate shady crimes in Veracruz. She had passion and dedication to her work.

Martinez was really interested in social issues, human rights violations. She was close to the people. That was her superpower.

Journalist Norma Trujillo, for Forbidden Stories

At the time, Veracruz was filled with drug trafficking and covert travel due to its geography.

The place had isolated footpaths in the mountainous forests, making it ideal for drug traffickers to hide out, extort migrants, and go undetected. Plus, long coastlines and international ports made it easy to import and export illegal products.

Martinez spent her life reporting on the real body count from shootouts that were underreported by authorities. And at the same time, she was investigating the extent to which the people in political power were affiliated with organized crime.

Thus, when Martinez discovered the story that would cost her her life, she knew it was the most dangerous investigation of her career.

Martinez’s death was the inspiration of The Cartel Project, intended to safeguard the life of the journalists who are risking their lives to get to the truth.

Martinez’s case

Martinez was brutally strangled and beaten to death in her own home. Still, her death was written off as a robbery gone wrong, and her case was underinvestigated. The Cartel Project, nonetheless, later took over what was left of the investigation to discover the following.

If a journalist like Regina, who worked for a national media outlet, could be killed, it could happen to anyone.

Journalist Andres Timoteo for Forbidden Stories.

By the time the federal investigator, Laura Borbolla, arrived at the crime scene, the police had already destroyed the fingerprints.

They claimed it was a robbery, despite the fact that everything in the house was untouched. Borbolla recounts that the crime scene was grossly mishandled.

But, Forbidden Stories was granted access to Martinez’s research after her death. They discovered that Martinez figured out where the thousands of people gone missing from Veracruz had gone. And, she had been quietly crafting a huge story.

What’s more, she even found out where some of the individuals were being buried. Martinez had followed up with gravediggers, and calculated that the number of people being buried in these mass grave sites had gone up by 1000% between 2000 and 2012.

She had gleaned knowledge of the fact that the last two political leaders of Mexico were complicit in this.

During this time, she had been quietly crafting a huge story that was about to be released right before her murder.

The Cartel Project: A tribute to Regina Martinez’s legacy

The commitment to truthful journalism that Regina Martinez demonstrated is a fire that lights the torches of a new generation of investigators.

And, it motivated The Cartel Project to create initiatives that would create awarness and raise security concerns over the well-being of its media heroes.

Journalists and fixers risk their lives in an effort to bring justice to Mexico, enact change in the regionm, and inspire others with their bravery. All in the memory of Regina Martinez.